Wikipedia, and other knowledge-sharing experiences

An account by Conrad Taylor of the 24 January 2019 meeting of the Network for Information and Knowledge Exchange.

Background

IN INTRODUCING THIS SEMINAR, Conrad suggested an alternative title could have been ‘Knowledge and the Social Machine’. This concept of the Social Machine was expounded by Sir Nigel Shadbolt in his opening keynote address to the Wikimania 2014 event in London, and was co-developed with Sir Tim Berners-Lee.

In ‘Technics and Civilization’ (1934), Lewis Mumford stated that the first machines were made of human components, tightly organised – that’s how the pyramids were built. The modern Social Machine is also made of people, who work together towards common goals, their collaboration mediated by networked computer technologies: a sociotechnical phenomenon. In this seminar, we examined how Social Machine methods and technologies can be used to collect and organise and disseminate shared knowledge.

This seminar had a two-part structure. The second half was modelled on method which NetIKX last tried out in November 2010, on the subject of ‘Information Asset Registers’, with three case studies examined in turn by table groups. However, we started more conventionally with a talk by Andy Mabbett, about one of the largest global projects in knowledge gathering in the public sphere – Wikipedia, and its sister projects.

Understanding Wikipedia and its sister projects

Andy Mabbett is an experienced editor of Wikipedia with more than a million edits to his name. Here’s a link to a ‘Wikijabber’ audio interview with Andy by Sebastian Wallroth (Sept 2017).

Photo of Andy at Wikimania 2014 in London, by Lionel Allorge. License: CC-BY-SA-3.0.

ANDY MABBETT is a prolific and experienced contributor to Wikipedia, where he goes by the nom de plume ‘pigsonthewing’ (a Pink Floyd reference — Andy was in the 1980s an editor of the Pink Floyd fanzine ‘The Amazing Pudding’, and has written three books about the group.).

Andy worked in website management and always kept his eyes open for new developments on the Web. When he heard about the Wikipedia project (founded in 2001), he searched there for information about local nature reserves — he is a keen bird-watcher — and couldn’t find anything. This inspired him to add his first few Wikipedia entries. He has been working with Wikipedia as an enthusiastic volunteer since 2003, and manages to make a modest living with part of his income stream coming from training and helping others to become Wikipedia contributors too.

Andy said he felt it should be easy to convince a roomful of professionals in the world of knowledge-sharing that we should love Wikipedia and its sister projects. The vision statement by Jimmy Wales for the Wikimedia Foundation, which hosts Wikipedia, says,

‘Imagine a world in which every single human being can freely share in the sum of all knowledge. That’s our commitment.’

For the ‘Wikipedians’, that is a motivation to contribute. They also do it because it is fun, because it is useful, and social. But the primary reason for many, including Andy, is the thought that there is some child somewhere in the world, perhaps in a developing country, who can’t get to school, but has got a mobile phone connected to the Internet; maybe that’s how she is able to understand her mother’s illness, or how the family can farm better.

Andy might compose a Wikipedia article about a jeweller or artist-maker from his home city of Birmingham; that may be the first time someone has written a publicly accessible biography of that person. He doesn’t create any new information, which would be against the rules of Wikipedia anyway. He puts together information already published elsewhere. Those sources may be as diverse and scattered as a line in an auction catalogue here, a museum record there; the Wikipedia article pulls that information together coherently, and gives links back to the sources. Andy hoped that in the future we might contribute too – either professionally, or in our private lives, contributing about hobbies and local interests, and places we visit on holiday.

Defining Wikipedia

What is Wikipedia? The strapline says, it is the free encyclopaedia that anybody can edit. It’s built by a community of volunteers, contributing bit by bit over time. The resulting content is freely licensed for anybody to re-use, under a ‘Creative Commons Attribution Share-Alike’ licence (CC-BY-SA) to be exact. You can take Wikipedia content and use it on your own Web site, even in commercial publications, and all you have to do in return is to say where you got it from (the attribution bit). The copyright in the content remains the intellectual property of the people who have written it.

The Wikimedia Foundation is the organisation which hosts Wikipedia: they keep the servers and the software running, and if you respond to the occasional banner asking for money, it’s the Foundation you are donating to. The Foundation doesn’t manage the content. It occasionally gets involved over legal issues, for example child protection, but otherwise they don’t set editorial policy or get involved in editorial conflicts: that’s the domain of the community.

Principles and guidelines

Wikipedia operates according to a number of principles, the ‘five pillars’:

- It’s an encyclopaedia, which also means that there are things that it isn’t: it’s not a ‘soap box’, nor a random collection of trivia, nor a directory.

- It’s written from a neutral point of view, striving to reflect what the rest of the world says about something. But it’s not a BBC Today version of neutrality. For example, on climate change, Wikipedia will say, this is the science and what most scientists agree with, but tacked on at the end it’ll say, by the way there are dissenting opinions. Not a 50–50 representation. The same would be true when discussing vaccines, or politics, or whatever.

- As already explained, everything is published under a Creative Commons open license.

- As regards the Social Machine aspect, there’s a strong ethic that contributors should treat each other with respect and civility – though to be honest, Wikipedians are better at saying that than doing it. Quite often, Wikipedia isn’t a welcoming space for female contributors, and women’s issues are not as well addressed as they should be. There are collective efforts to tackle that imbalance e.g. with training sessions for female editors, but just as in the real world the community has its share of misogynists and racists, or at least, people who carry biases. That could affect the way contributors interpret history, but Wikipedia is hardly unique in that respect, as an inspection of the mass media will attest.

- Lastly, there is a rule that there are no firm rules! Whatever rule (or norm) there is on Wikipedia, you can break it if there is a good reason to. This does give rise to some interesting discussions about how much weight should be given to precedent and established practice, or whether people should be allowed to go ahead and do new and innovative things.

Having just said ‘there are no rules’, Andy told us the most important two rules on Wikipedia! The first is the General Notability Guideline (GNG), which states that a Wikipedia article should be about something that has significant coverage in multiple reliable sources, independent of the topic. Should you want to write an article about the company you work for, or your grandfather, or some thing you are interested in, the GNG will apply. ‘Significant coverage’ means for example articles, such as obituaries in The Times and The Guardian, articles in publications with a reputable editorial process, mentions in books from serious publishers who employ editors and fact-checkers. Wikipedia doesn’t want sources such as your blog, or the vanity press, though there may be exceptions.

Wikipedia also insists on Verifiability. So if you tackle a subject which validly meets the GNG criteria, each thing you say about that subject should be backed up with a reference to a reliable published source. For example, you can’t say ‘this is the ugliest building in Marylebone’ – that’s just your opinion. You can say however that Nikolaus Pevsner declared that building to be the ugliest building in Marylebone, in such-and-such a volume of The Buildings of England.

The use of citations is how readers of a Wikipedia article can be reasonably confident that what they are reading is reliable. If verifiability is really important to you – say, for example, your GP has prescribed a medication for you and you are pondering whether to take it – then for goodness’ sake don’t take the Wikipedia article’s word as gospel, but go and read the cited sources for that information.

(That is the ideal. Of course, reading Wikipedia you’ll often see where an editor has critiqued an inadequately documented article with a ‘citation needed’ tag.)

In Wikipedia, all contributors are theoretically equal and hold each other to account. There is no editorial board, there are no senior editors who carry a right of overrule or veto. ‘That doesn’t quite work in theory,’ added Andy, ‘but like the flight of the bumblebee, it works in practice.’

Fact-checking and its undesired consequences

How well does this work? In September 2018, newspapers ran a story that the Tate Gallery had decided to to stop writing biographies of artists for their Web site; they would use copies of Wikipedia articles instead. The BBC does the same, with biographies of musicians and bands on their Web site, also with articles about species of animals. The confidence of these institutions comes because it’s recognised that Wikipedians are good at fact-checking, and if errors are spotted, or assertions made without a supporting reliable reference, they get flagged up.

But, there are some unintended consequences too. Because dedicated Wikipedians have the habit of checking articles for errors and deficits, Wikipedia can be a very unfriendly place for new and inexperienced editors. Andy’s been editing Wikipedia so long (with over a million edits and counting!) that he can remember the early days – someone could just start a new article with a handful of bullet points, in the expectation that others would come along and flesh out the details. These days, such a tentative start would be deemed not good enough, and some other editor would remove it: there is now a steeper learning curve.

Occasionally, someone will flag something you have written as needing further attention. Andy showed as an example, an article by a novice contributor whom Andy was coaching, which collected eight such critical ‘flags’. That can be terribly off-putting and crushing, and Andy is one of a band of Wikipedians who try to influence more experienced editors to be welcoming and kind to new editors. In talking about the social aspects of Wikipedia, said Andy, it’s important to be honest and admit that this kind of rough behaviour goes on. People can get so zealous about fighting such things as conflicts of interest, or bias, or pseudo-science, that they can get quite aggressive in dealing with others who are actually trying to make constructive edits.

Hundred of Wikipedias – in different languages

Screen capture shot of Chinese Wikipedia page about the Silk Road. Here cropped to show just the ‘infobox’ panel which is at the top right of many Wikipedia pages.

Thus far, Andy had talked about Wikipedia as a singular thing – and for most people in the UK of course, that means the English-language Wikipedia, which is the biggest in terms of content – 5.79 million articles (at the time of speaking!). But there are nearly 300 Wikipedias, in different languages. Several have over a million articles, some only a few thousand. Some of the Wikipedias are in languages threatened with extinction, and they constitute the only place where a community of people is creating a Web site in that language, to preserve the language as much as to preserve the knowledge. Some of those minority languages are politically threatened by oppression, or have been in the past, such as Catalan and Basque. There’s a Wikipedia in Cornish, and in the Australian language Noongar. People able to work in more than one language have a very special value to Wikipedia, helping by translating pages between the different language versions.

The sister projects

Wikipedia also has a number of ‘sister projects’. Here are a few:

- Wiktionary is a multi-lingual dictionary and thesaurus.

- Wikivoyage is a travel guide, useful for tips about travel and accommodation and eating, and cultural norms.

- Wikiversity has a number of learning models so you can teach yourself something – from nuclear physics to baking a cake.

- Wikiquote is a compendium of notable and humorous quotations, each one fact-checked and tracked back to its true source.

- MediaWiki is the software that Wikipedia runs on, a kind of Content Management System (CMS). Of course, there is a wiki that documents that software, tells you how to use it and even how to install it and set up your own wiki system – which could be for a staff handbook, or product catalogue, or whatever you desire. It’s free software, Open Source, and there is a community of people who can help you to install it and get it running.

Wikidata

Andy thinks the Wikidata project is probably the most important of Wikipedia’s sister projects, in terms of the impact it is having, and its rate of expansion. But, it has to be understood in the context of Wikipedia. Andy drew our attention to the ‘info box’ which appears to the right side of many Wikipedia articles (an infobox in Chinese Wikipedia is shown above).

As an example, Andy showed us the one for the painter Claude Monet. It contains basic facts such as his place and date of birth, his place and date of death, the facts that he was French, was a painter, was part of the Impressionist movement; some of his more notable works; and the names of his wives and children. With data like that, you can compare one person with another, programmatically.

In 2007 or thereabouts, Andy initiated a project to make facts in these information boxes machine-readable, by adding microformat mark-up behind the scenes, so you could use a Web browser to parse that information and compare it with the boxes on other pages. From that came the idea of gathering all this information centrally. One advantage is that the information is easier to share across different versions of Wikipedia (though, of course, using an appropriate translation). Consider that in the Wikipedia family, there are possibly 200 wikis with an article about Claude Monet, and that data was being stored in 200 different places. Now, it is stored in a central database. If somebody now alive and documented on Wikipedia were to die tomorrow, a change to the database would update all the pages using that data.

That’s how Wikidata got started, and the community then developed an API and a SPARQL query engine and applied an open license to the data (CC0, which means no attribution is required). This means the data can be used by any other project in the world. Andy showed us what the Wikidata entry for Claude Monet looks like. Each item of data is given a unique identifier, the ‘Q number’, and you can use those identifiers in your systems. There are identifiers for millions of things – for people, for papers and other documents, for places. Using those identifiers can help your system become more interoperable with others.

Querying and exploiting Wikidata

Again, via the Wikidata API and SPARQL query system, it has become possible to ask Wikidata, ‘Give me all the scientists who studied at this university’, or ‘Give me all the French painters who died in this year.’ This is being used in various applications, across industries – Andy recounted how, when flying to a conference abroad, the airline had an application that told you about various places the plane was flying over – and all the information was being pulled in from Wikidata.

As in Wikipedia, data should have references – it’s good to know where the facts have been sourced from. This could point to another work of reference, such as a bibliographical database, or else through a citation to a publication.

Wikidata also records identifiers lifted from other public sources – for example, ISBN and ISSN for publications. For listed buildings and scheduled ancient monuments in England, the English Heritage identifiers are used. The British National Formulary provides identifiers for drugs. Chemistry databases provide identifiers for chemical substances. For actors and television personalities, the Internet Movie Database IMDB serves this function.

All the properties in Wikidata (for example, someone’s data of birth) also have a unique identifier, the ‘P series’ of numbers. Even properties can themselves have properties, an example being the British Library’s equivalent of that property, in their cataloguing system.

And all of this is Linked Open Data. Via a SPARQL Endpoint, complex queries can be fired at Wikidata, and there is a ‘wizard’ to make that easier to do. Imagine going to your local reference library and saying, ‘I want a list of cities in the world with a female Mayor, and I want that ranked by the size of the population.’ Your librarian would run away screaming. It takes Wikidata less than second to formulate the response to that query. The data isn’t always complete, of course, because Wikipedia needs more volunteers to add stuff and keep updating it. But where the data is there, querying it is very fast and very powerful.

There are also data URIs, which is different from the view for the humans, and those can be used in your Linked Data application. Or, you can take a mass data dump – several gigabytes, but Andy knows of a few universities who have done that to run massive queries and analysis, which they can do it more quickly locally. If you opt for the full data dump, you can also opt for incremental updates by the week, day or hour.

Wikidata may store data items about entities that aren’t mentioned anywhere in any Wikipedia. For example, there is already an item for every street in The Netherlands, courtesy of a nice database maintained by the Dutch government. There are also more items about more nebulous things such as concepts – ‘knowledge’, ‘love’, ‘hate’, ‘taste’ etc.

There can be an item about every living species on the planet (extinct ones, too…). Lots of other organisations have databases of species; what Wikidata does that the others don’t is, when the item says who named the species, that person will also have a data item that says to whom they were married, when they were born and died, and where they studied. There is a web of data within Wikidata that maybe doesn’t exist outside of it.

Wikidata has lots of information about movies, popular entertainment and the high arts, books, works of art – and those ‘info boxes’ on Wikipedia articles about works of art are increasingly being populated entirely from Wikidata. This also makes it easier for other-language Wikipedia articles on those subjects to be constructed.

Magnus Manske has produced an experimental tool called ‘Listeria’ – list-generating software based on Wikidata – which can create whole Wikipedia articles which are lists of things. Andy showed an example – a list of all lighthouses in the Netherlands; an automated script updates it once a day, so if a contributor adds more data about one of the lighthouses, that will get included in the next build, in all the languages of Wikipedia using this tool.

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons is the repository for images, video, audio, PDF files of scans of books and journal articles and the like. Either these resources have been contributed under an open licence – the copyright-holder has said that anyone can use this so long as he or she gets attribution – or they are out of copyright: very old books and artwork, and items in the public domain. More contributions are always welcome, so if your institution has a collection of paintings of historical figures, and you have digitised those, please give those digitisations to Wikimedia Commons to illustrate the biographical articles about those figures.

Amateur photographs are also welcome – they may be views of historic buildings, other locations, landscapes; they might be unusual bits of equipment your company works with, or unusual vehicles. If you take photos with a tablet or smartphone, you can even get an app that uploads the photo straight into Wikimedia Commons, together with a few words of description which you add.

Wikimedia Commons is now starting to use the same database software that Wikidata uses. So in future, you’ll be able to add statements which will be machine-readable, and query the contents of Wikimedia Commons in a similar way.

Wikicite

This is a project nested within Wikidata, and covers about 30% of all the data. It started when someone suggested making Wikidata items about all of the works (books, journal articles, press reports etc) cited in Wikipedia –then, instead of putting all the citation metadata into every Wikipedia page that uses that reference, all those articles could just be linked to that media item. As it developed, the scope expanded – one reason being, it was easier to add all Joe Smith’s published papers than to figure out which of them were currently cited in Wikipedia articles! Automation tools have been added to make this easier.

Andy extolled the virtues of ORCID identifiers. This is a unique ID which authors can apply for – it’s rather like an ISBN for books, but it’s for the person who writes something – a book, a scholarly paper, an article, a presentation for a conference… you can register yourself for an ORCID identifier. It looks like a credit card number (16 digits in groups of four). You can add those to your works, and even if your name is the same as another person (or, you have changed your name) your unique identifier will disambiguate you. You can then list your works on the ORCID Web site. ORCID has an API too, which is helpful to the Wikicite project: if an author’s ORCID ID is known, Wikicite can ‘raid’ the ORCID profile to add all that person’s works to Wikidata; then they can be linked to their co-authors, whose works they have cited, which other works cite theirs – a whole web of linked data.

There are tools that can read that structured data, and display it for you – such as Scholia (see https://tools.wmflabs.org/scholia). Using Scholia, you can do things such as discover who co-authored with whom, or which universities published on a particular topic.

Anyone [with the capability] can build tools that build on Wikidata, and a friend of Andy’s who was a Wikimedian-in-Residence at the University of Oxford’s Bodleian Library built a tool as an explorer for works of art in their museums. The Bodleian’s catalogue software is pretty poor, so he imported all the data into Wikidata, added images of all the items, and provided his colleagues and their visitors with a much better interface. He also built a tool to do something similar for a global collection of astrolabes, using which you can browse information and images as if they were a single catalogued collection.

For people who have a dataset they’d like to contribute, but don’t know how, there’s a tool called QuickStatements (again, by Magnus Manske) which can read stuff in spreadsheet format and convert it into Wikidata.

Andy also mentioned the campaign One Librarian, One Reference (#1Lib1Ref), which invites all librarians to add a single citation to Wikipedia articles that currently are deficient in them. Andy encouraged everyone present, whether a librarian or not, to participate.

Wikisource

This is a repository, an online library of out-of-copyright and Open Licence texts. Quite a few library sites hold scanned images of books – the British Library, for examplke – and some have fed those scans to an Optical Character Recognition process, but that generally produces many transcription errors. The Wikisource project has developed a MediaWiki extension called ProofreadPage, which volunteers can use to read an OCR-produced text and see it side by side with the scanned source, and thereby make corrections. The corrected text is then machine-readable, searchable, and can be downloaded as an e-book.

Sampling people’s voices

Andy has a project he’s quite passionate about and would like some help with. Do we know somebody who has an article on Wikipedia? If so, could we record a small sample of their spoken voice? About 10–15 seconds would be ideal, saying their name, when and where they were born, and a detail or two of their career, and it doesn’t need any fancier recorder than a mobile phone in a quiet place. That sample can then be included in the ‘info box’ on the page about that person. That will give a record of what they sound like, and crucially, how they pronounce their own name.

Read more at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Commons:Voice_intro_project

Wikimedians in Residence

This project is where Wikipedians work inside an institution such as a learned society, a museum or an art gallery, a university or similar. The aim is to add to the Wikimedia Foundation’s various projects using the knowledge and information and media resources of that institution. The visiting Wikipedian can teach the institution’s staff or members how to edit Wikipedia, and pictures to Wikipedia Commons, etc. So far, about 150 to 200 people have acted in this role – Andy himself, several times. The role can be voluntary or paid, full or part time, done on site or remotely.

In closing, Andy pointed out that in 2012, the ‘Wikimania’ worldwide conference was in Washington, D.C. The keynote address on that occasion was given by David Ferriero, the Archivist of the United States. And he said, ‘I am about to say something, and if it helps you to quote this when you talk to other people, please do…’ He had appointed a Wikimedian in Residence, who helped add much of their collections to Wikipedia and Wikimedia Commons, and he said, ‘If Wikipedia is good enough for the Archivist of the United States, maybe it should be good enough for you.’

PART TWO

Table-group exercise format

I devised the format for the second half of the meeting using a model we last tried in November 2010, at our seminar on the subject of ‘Information Asset Registers’.

When a seminar focus on Wikipedia was first proposed, some Committee members wanted to look at other scenarios using a shared Content Management System to gather and share knowledge. As we have had several meetings about Sharepoint, I excluded that option, but invited Steve Dale to talk about the Communities of Practice platform and the Knowledge Hub set up by the Local Government Association, and Mark Barratt of Text Matters to talk about a wiki he’d set up on the Atlassian Confluence platform for a coalition of NGOs which provide international disaster relief assistance. Sara Cullen, who is a member of the NetIKX Committee, undertook to explain how her company uses Jazz software to share knowledge internally.

As the date drew close, Steve Dale could not come because of a family commitment, but Richard Millwood who was also involved in the LGA project, and has set us several distance learning systems, stepped in at short notice. And on the day, Mark Barratt fell ill! But Sara was all prepared, and Andy Mabbett agreed that instead of adding a Q&A session to the end of his talk, he would make himself available as a third ‘case study witness’. So we were all good to go.

Three tribes, three witnesses

This is how it worked. We divided the participants into three table ‘tribes’ with a ‘tribal elder’ to manage the discussion flow, and a totem animal for each – the Elephants, the Leopards and the Zebras. People sat in their ‘tribes’ for the rest of the afternoon. Then we had four time-limited shifts. In the first shift, Andy joined one table group, Sara another, and Richard the third (not Richard the Third!) In the second shift, each ‘witness’ moved to a new table for interrogation; and similarly for the third. The fourth shift was when we pooled our observations.

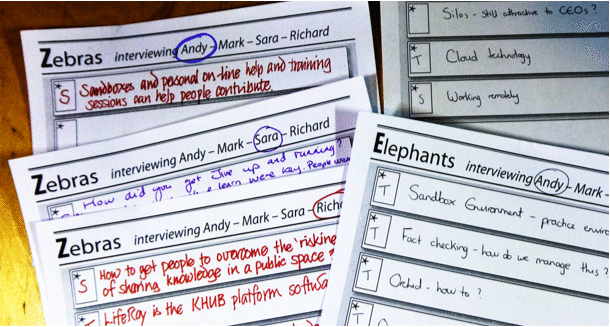

A few of the ‘observation forms’ on which our table-group ‘tribal tribunals’ (elephants, leopards and zebras) jotted down their observations. These were later displayed to the whole room using the document camera.

I had printed off some forms, and asked the table groups to think of these case studies as Social Machine examples, and write down observations upon these forms, to share in the final plenary session. What stood out in each case as helping or hindering knowledge sharing? And was that a social dynamics issue, or affected by the technical features of the software system, or something else? These cards comprise ‘evidences’ of our table group thinking and have helped me to write up this account — after all, I could not listen in to three tables simultaneously!

How did it go?

Did the experimental format work? Well, I think the participation was enthusiastic, and the feedback mechanism was quite novel. On the down side, I think it was stressful for the ‘presenter/witnesses’, and each workshop shift at about 25 minutes was a bit too short. But I think this method is worth adding to the NetIKX ‘playbook’ of workshop session techniques, and something to learn from.

In the condensed narrative below, I first describe for each witness speaker how the conversations went at the Table of Zebras, where I was sitting, as I have a recording of those. Finally, I shall describe the ideas-pooling final session and the matters which were noted there.

A conversation with Andy Mabbett

Our herd of Zebras asked Andy questions: one of mine was about mediating the relationship between Old Hands and Newbies – this is found not only as an issue in Wikipedia, but in many ‘social machine’ situations, such as email discussion lists. Indeed, the origin of the ‘FAQ’ list is because people newly joining a support email list for software kept asking the same old questions again and again, much to the annoyance of the Old Hands. Maintaining appropriate adult behaviour in such groups is also the origin of the concept of ‘Netiquette’.

Getting people aligned to the modus operandi and norms of a social machine platform can be done in training sessions such as those Andy runs for new Wikipedians, but how can this be done at a distance? Andy replied, they have several tools for this. There are forums within Wikipedia specifically set up for new editors to seek help and advice. You can place a tag on your user pages which indicates, ‘I’m new here, can anybody help me?’ There are also ‘sandboxes’ where people can experiment without touching any published page, and then you can share that experiment with someone more experienced to ask for guidance. There are tutorial pages where you are asked to try out various tasks, such as adding a citation. Wikipedia tries to cater for a variety of learning styles. And then there are also real-world meetups.

Generally good advice is not to start your Wikipedia career by writing a new article! It’s better to tiptoe into Wikipedia space by doing something like adding citations, or a small additional statement with a citation. ‘To write a good Wikipedia article from scratch, you have to excel at something like ten different things, and that’s difficult when you are new,’ he said, partly because of the [critical] culture.

Andy said more about Wikipedia culture. The deeper in you go, the more you may experience the less nice side. ‘There are some vicious people; there are people building their little empires.’ There are some, and Andy admitted he can be like this, who are used to talking to other experienced editors, and (as in many trades) they use shorthand or jargon which other users might experience as curt. And that could involve being a bit hostile (or blunt) ‘because if I’ve known you for 10 years, and you keep making the same mistake, of course I’m going to tell you off!’

Asked how the Wikipedia communicates the positive and altruistic values he started his talk with, Andy mentioned a few ways. There are face to face events for editors, and teach-ins. People are encouraged to contribute in non-text-editing ways, such as adding pictures to the Commons. There have been writing competitions, particularly within institutions working with a Wikipedian in Residence. There’s also an effort to help people find their niche. There are Wikipedia editors who write only about postboxes! One guy writes only about one American football team – and every week, for years, he’s been updating the page about them, and related pages about the players. One person only corrects grammar, and has done so for many years.

Graham Robertson was curious about the ‘submissions’ process. Andy said that provided the licensing is open, text can be cut and pasted from a Word file. There are transcription tools. If there is something obscure in PDF, it might be added to the Commons as PDF; but if a lot of people will want to read it, it’s better to transcribe.

Clare Parry wondered about quality control in the case of translated content. Andy replied, if something gets translated into French, then French editors will go take a look to make sure it’s OK. As for very small language groups, the Foundation won’t support there being a Wikipedia in that language unless there are about 20 people committed to working on it.

A conversation with Richard Millwood

Richard said he was appearing as a substitute for Steve Dale, talking about work they were both involved with in 2007–8 for the ‘Improvement and Development Agency’ (IDeA) of the Local Government Association. It has been some time since he has spoken about it. What they were helping to establish was a ‘Communities of Practice’ platform so that people with similar jobs across the 450 or so English local authorities could share ideas, compare notes and learn. The problem they were trying to solve is that these people might be facing very similar problems, without access to a peer group to share solutions, analyses and ideas. The platform grew to attract several tens of thousands of members, participating across hundreds of different topic-oriented forums.

That work then evolved into the Knowledge Hub project; Steve Dale was more associated with that, and with structuring knowledge and information ‘harvested’ by the CoP platform; and how knowledge might be steered to the users without them having to go hunt for it. The idea was that if users could register their interests, the Hub would use this data to direct information resources towards the user – including contact with others with similar interests. As for Richard, he had been more concerned with the discussion forum aspects, and building the online community.

Richard introduced the idea of a Community of Practice, a term promoted within the field of knowledge management by Etienne Wenger; related terms are Community of Enquiry (which is what Richard had previously built in university distance learning), and Community of Interest (where people might come together around a shared hobby, a shared interest in industrial archaeology, or some such).

In thye project they’d asked themselves, why does social media work in such a vibrant way? How can this energy be kindled, and trust built at the same time, such that people will come and be prepared to share their knowledge in an online space? In local government there are many who work in areas that are problematic, confidential and reputationally risky, so there were always going to be difficult issues.

The platform which supports the Knowledge Hub was created by MYKHUB.net. See http://www.improvementservice.org.uk/knowledge-hub.html

A member of our group who works at Heritage England explained that within the Knowledge Hub they have built a ‘Heritage Workspace’ which is a grouping or meeting point of groups around related topics. This balances the majority tendency of people forming KHub groups to want access to be restricted to group members only, for privacy reasons. There’s a big topic at the moment around guidance for local authority people working with heritage assets, and although KHub does provide some limited wiki functionality, they’d found it more convenient to set up something more fully-featured on the Liferay platform.

The lifespan of the CoP platform and KHub has gone through rough and rocky seas. The leadership of the LGA seemed to have lost interest; the management went through several hands. For a while it was run by Liberator, then spun out into an independent company, which also has an association with PlaceCube (https://www.placecube.com/)

A topic which arose in this conversation between Richard and the Zebras was the importance, when using a platform for what can be quite sensitive knowledge sharing and discussion, of knowing that the community platform is in safe and trustworthy hands – especially in the light of controversies surrounding Facebook. It’s important to know that all the KHub servers are based in the UK.

Sara Cullen on the uses of Jive

Sara brought a different style to the table. She had a computer presentation to take us through. She works for a publishing company, CRU International, whose topic is metals and mining, with about 300 staff distributed globally. The company has a knowledge and learning strategy, based on connecting people and collaborating, and learning from each other. They deploy a range of tools and methods, and what Sara was going to tell us about – their Jive social platform – is just one activity amongst others.

Jive is a social collaboration tool. They chose it for three main reasons. One was, because Jive lives on the cloud, and this was important because the IT department didn’t want to help! Another was, it was easily integrated with their existing systems, based around Microsoft Office. Finally, it was on the Web, and this was helpful because CRU staff were often travelling or with clients, and they hated using the company’s own network. As the company was expanding overseas, the remote offices were always complaining about trying to work on company shared drives.

Previously, the company had a traditional-style Intranet and a ‘people finder’ and blogs. When they implemented Jive, internally they called it ‘the eHub’. Sara’s fellow managers got quite excited and saw that it might be used to collaborate internationally on projects, and to support their Communities of Practice, which got going at about the same time. It was also possible to use it externally, for example with clients.

Was it successful? Sara thinks so. You could use the eHub to find out what expertise was available in the company, their industrial experience, who spoke what language, etc. Something as simple as being able to see photos of people made the worldwide community feel more real, and helped new people be recognised and integrate faster. She encouraged her peers who had ‘bought into’ the eHub early, to champion the eHub and advertise its benefits to other colleagues. Yes, Jive was a great tool, but the role of people promoting it and showing the way was key. In terms of knowledge management, they also put their learning materials on the eHub, which was great for the ‘newbies’. It was particularly loved in the overseas offices. For the first time, they really felt part of the company.

What were the lessons learned? Well, it improved on existing communication channels, and it was a benefit to be able to access it from anywhere through a Web browser. The role of early adopters as champions was key, and it was important that the CEO was an enthusiast. Sara reckons that the Expert Directory, for which she was responsible, turned out ‘a bit dull’ and had there been more money, she’d have loved to have got someone in to make it more creative.

In 2017 Jive was bought by Aurea, who have rather distorted the platform to suit their purposes, and the quality of support went down. Indeed, the whole platform collapsed for several days under the new ownership, and CRU users felt bereft and stranded, having come to accept their eHub as part of working practice. This is one of the perilous things about engaging with Software as a Service – you can’t predict what will happen in future. You have to accept that social collaboration tools like this are going to change over time.

She thinks that their eHub doesn’t now fit within the organisation quite as well as it did a few years ago. The milieu has also changed with the onset of GDPR, and Jive posed some security risks because you needed only user name and password to get onto it. As for the Communities of Practice, some flourished because people took ownership of them, but others languished.

Pooling observations

As explained above, each ‘table tribe’ had been given forms on which to record brief observations about the technical and social factors affecting the success of Social Machine type platforms as a way of sharing knowledge. We now had very little time left at the end of the seminar, and Conrad paraded some of the cards for the audience by projecting them via the document camera. Here I simply display some as a bullet point list.

- Champions as early adopters and spreaders of enthusiasm – as Sara had illustrated. (Deliberately starting with a small group of enthusiasts also helps to trial the system.)

- Openness, versus confidentiality and security (was an issue for the IDeA KHub).

- Issues of balance and neutrality, which have arisen in Wikipedia.

- Useful to be provided with a safe sandbox environment for learning and practicing.

- Online support forums.

- How do we check facts that have been asserted?

- Breaking down knowledge silos – Dion noted this is as much a problem now as it was 25 years ago!

- Advantages of systems based on cloud and Web technologies, using Software as a Service. But there are risks with SaaS too, as Sara’s story shows.

- Help people to find their niche, the ways in which they feel comfortable in contributing.

- An Expert Directory can help especially in a corporate setting: knowing with whom to collaborate.

Finally, Conrad asked the audience how they felt about our experimental seminar format. The reaction was overwhelmingly positive. Dion thought as a discussion method it could improve with some more iterations. There was a mix of reactions to suggestions that the period for each discussion was too tight; some agreed that more time would be good, some felt that the pressure of time also brings some benefits and focuses minds.

— Conrad Taylor, May 2018