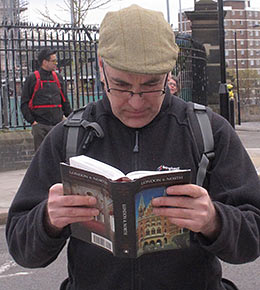

Conrad, wearing on his belt the UHF radio receiver, hanging below that the Marantz recorder, digital recorder, and a Røde PinMic micrphone on his chest.

WalkieTalk is an informal project, currently a series of experiments by Conrad Taylor and Danny Budzak. We are recreational walkers, with interests in urban and intellectual history, media and culture, and knowledge management, amongst other things. We walk London at weekends.

During a WalkieTalk, an audio recording is made of the conversations that occur while we explore a territory with our eyes and ears open, collating our fresh experiences and impressions with what we already know and can recall.

What’s here

The initial contents of this sub-site have been assembled to support Conrad’s participation in events at the Cass Business School in London, on the week commencing 22 April 2013 — in particular, the workshop on 22 April called Walking, Journeys & Knowledge. Those events have been organised by the School in conjunction with the arts project Motiroti under the title ‘multipliCities’ and you can find out more about those events here.

- We have a longer text about the theoretical framework for WalkieTalk in relationship to Guy Debord’s concept of the dérive and some practices in knowledge management — also a description of our methods for turning a walk into an audio product. This text will soon be brought online and expanded. For now, you can download the one-page PDF ‘Manifesto’.

- Our first large-scale experiment in ‘WalkieTalking’ took place on 14 April 2013 on a five-hour London walk encompassing Holborn, Fitzrovia, Marylebone, Regent’s Park, Camden Town and Kentish Town. The finalised edited audio of the conversation on that walk, with ambient sound, is available for download here as a one-hour stereo MP3 file (Filesize 57.6MB).

- Also here below the line, a few photos and captions will soon be coming, showing how we were equipped to make these recordings.

The equipment, and how we use it

Each of us wears a discreet omnidirectional

Lavalier microphone mounted on shirt or jacket, about 20cm from the

mouth. One of us, Danny, has his lapel mic plugged into a belt-worn

UHF radio transmitter, the same kind of equipment used by speakers

at a conference (Sennheiser G3). Conrad is in charge of the technics;

he carries beneath his jacket a digital audio field recorder (Marantz PMD-661)

with two distinct XLR input sockets for Left and Right channels, the kind

of thing a radio journalist might use on assignment. His own lapel mic

is plugged into one socket; the other receives input from a Sennheiser

G3 beltpack UHF receiver. With fresh batteries, we can record for up

to three hours continuously, and we carry spares.

Danny usually carries the relevant local volume of Pevsner’s ‘Buildings of England’ for on-the-spot research about the buildings we encounter en route.

The placement of the microphones lets us capture clearly what each of us is saying, also the ambient sound, including conversations with people we meet along the way. Conrad keeps a crafty eye on the gain level meters, and also wears a lightweight set of closed-back monitoring headphones, of the sort which fold down so they are comfortable sitting around the neck. They need checking only occasionally.

The technique works best in reasonably quiet street environments. Wind-noise on the mics is a challenge in more open landscapes and we must experiment further with windshielding. The WalkieTalk recording methodology should also work brilliantly in museums, galleries etc.

The ‘raw product’ is a bunch of stereo WAV uncompressed audio files. These are roughly logged to make editing decisions; unwanted passages are removed using Audacity editing software. The continuous track may also be chopped up at this point into ‘chapters’, and some introductory narrative may be recorded for insertion. Adobe Audition software lets us bounce the Left and Right channels into independent tracks in a multitrack editing session, so the extreme stereo split between left-speaker and right-speaker can be softened into a passable stereo mix. The edited result is exported to a mixed-down stereo file which is then converted to MP3 format for distribution.

Going forward, we want to pay better attention to the need of the audience to ‘see’ what we are seeing — experienced BBC reporters (e.g. on Farming Today) are good at doing that. As an alternative, we might look at how to integrate the audio product with photos we take, map imagery and other visuals into a multimedia presentation.